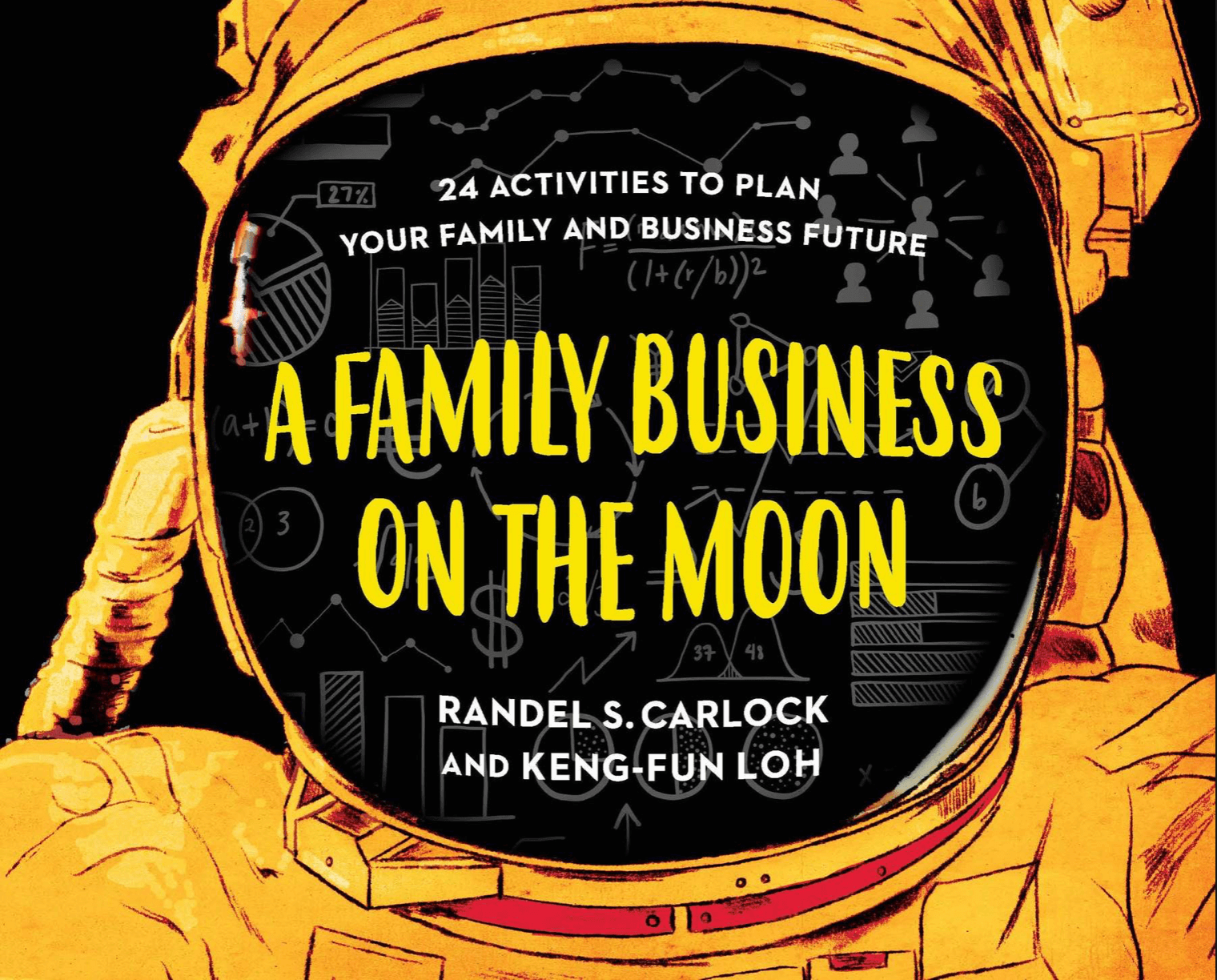

Randel Carlock takes a singularly pragmatic approach to the subject of family business management. His latest book, A Family Business on the Moon, written with Keng-Fun Loh, is not a textbook or self-help volume. Instead of describing family business dynamics through dense theoretical terminology or the lens of case studies, their book gives readers access to a lifetime of aggregated wisdom from teaching and consulting with family businesses around the world for over 25 years, condensed into a series of practical exercises.

Carlock and Loh emphasise the human dimension. They assert that consulting efforts often fall short by focusing exclusively on business planning at the expense of planning for the family. A Family Business on the Moon demonstrates the importance of focusing on both aspects simultaneously to sustain long-term success in the family enterprise.

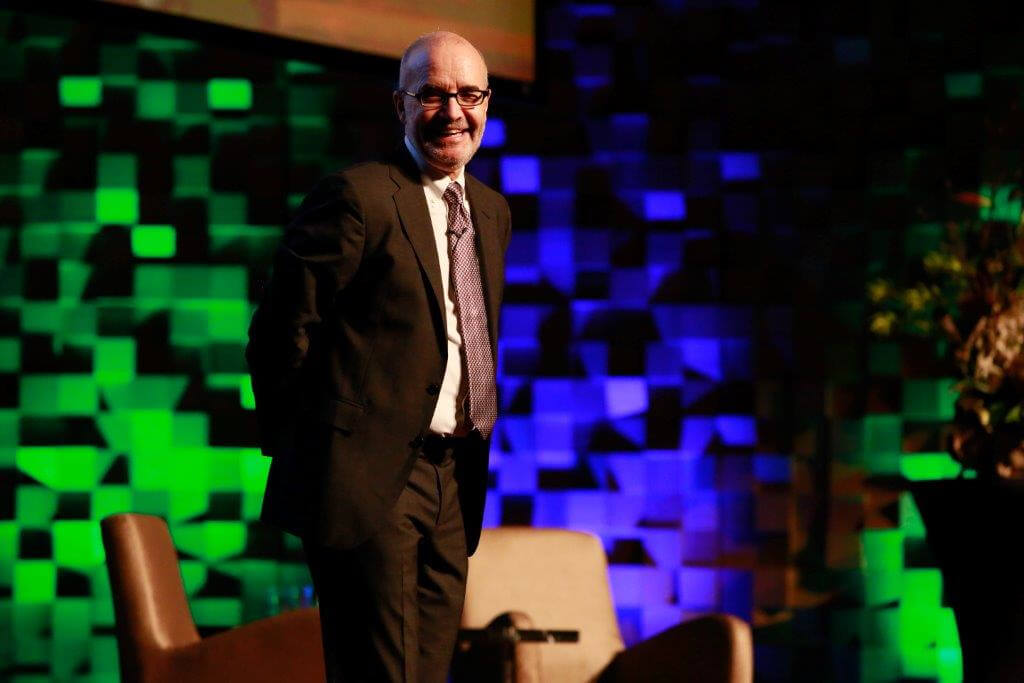

A Family Business on the Moon is Prof. Carlock’s sixth book on the topic of family business strategy. His years of experience as a CEO and family business consultant, coupled with his postgraduate degrees in both entrepreneurship and psychology, uniquely qualify him to address the challenges of family businesses across industries and geographies.

Recently, Tharawat Magazine had the opportunity to speak with Randel Carlock about the importance of the Parallel Planning Process (PPP), the critical task of developing talent within family businesses, and why we should think of family businesses as family enterprises.

Image courtesy of Randel Carlock.What made you decide to focus on the field of family business?

Family business wasn’t yet taught as an academic discipline when I completed my doctorate in entrepreneurship 30 years ago. Recognising the need for a dedicated course, Wendy Handler, Nancy Bowman-Upton, and I came up with a curriculum and began teaching it at our institutions.

I decided to switch my focus from entrepreneurship to family businesses because I was attracted by the challenge. It’s an exceptionally diverse and multifaceted subject, encompassing psychology, management and leadership. It’s a human discipline, and for our MBAs and business students, understanding its humanity is imperative. You can’t work effectively in the family business space without emphasising this aspect.

Business schools often assume that business people make only rational decisions, which is simply not true. None of us is wholly rational – family businesses prove this truism. It doesn’t necessarily mean we’re irrational; it just means that emotional factors and intuition also play a role in the decision-making process.

Business schools often assume that business people make only rational decisions, which is simply not true. None of us is wholly rational – family businesses prove this truism. It doesn’t necessarily mean we’re irrational; it just means that emotional factors and intuition also play a role in the decision-making process.

What motivated this latest addition of yours to the family business literature?

The idea originated with a next-generation member of the Bata Shoe family when I was working with them at INSEAD. During an exercise to explore family vision, he said, ‘We’ve got so many stores on earth; maybe we should put a shoe store on the moon.’ The metaphor resonated with me. In the front of the book is an illustration of a shoe on the moon – a homage to the Bata family’s imagination.

As for intent, we wanted to create a resource beyond the purview of normal business management books. In my opinion, books that address the subject of family business can be categorised into three distinct types.

The first is the car crash, a story of consummate failure with no practical appeal or application. The second type is characterised by a hero saga and reads like a novel. These biopics are easy to get through, entertaining and typified by a liberal attitude towards truth, which means they are ultimately useless as a resource for family business.

The last category is reserved for the advice of an expert. However, the existence of experts in family business is a fallacy. No two families are alike and, as such, the solutions to the challenges they face cannot be found in a generalised self-help-style manual.

Find out more about the book here.

How did you come to collaborate with Keng-Fun Loh?

Keng-Fun has a keen interest in business families and comes from a banking background, having worked for Citigroup and Credit Suisse in the United States and in Asia. I met her at Credit Suisse when I was working with them on their family business program.

We have much in common, and I was impressed by the extent of her expertise, developed wholly outside of academia. She helps keep my writing functional.

Every day, I have to remind myself that, in the family business space, I’m not an academic – that’s not the goal of my work. I’m a human being, a business person and a leader.

What’s the starting point for families who go through the process outlined in your book?

Families must prepare by planning and communicating. We find that most family business members have a difficult time expressing their aspirations explicitly. For example, it’s hard to say, ‘Dad, I would like to be a leader of our family business. Mentor me.’

These barriers aren’t limited to any specific geography; they exist everywhere, in all cultures. I’ve never met a family, anywhere in the world, that would be comfortable with the questions: ‘When am I going to get to be CEO?’ and, ‘How much wealth are you going to leave me?’ These questions, as disquieting and taboo as they are, must be answered one day, and it’s better to prepare for this eventuality.

This book is designed to establish a dialogue, and we start with values. If your values align, you’re 80 per cent of the way to building a powerful team.

Families must prepare by planning and communicating. We find that most family business members have a difficult time expressing their aspirations explicitly.

Your book reiterates the importance of PPP. What does it stand for and what can it do for families?

PPP stands for Parallel Planning Process. The idea came from a book that John Ward and I wrote about 15 years ago titled Strategic Planning for The Family Business. We introduced the concept of parallel planning, which originated from my work with the Cargill family.

I was a consultant to the Cargills, and they had business strategies and plans in place that were 20 or 30 years ahead of their competition. They were brilliant business people but struggling with their family challenges, so we started to think about ‘strategic’ planning for the family.

Our idea was to better align their family and business planning and actions. They had strong family values, so we decided to anchor their family and business plans around those values. With this parallel approach in mind, we then examined vision, strategy, investment and governance.

Governance in the family is agreements and family meetings. In the business, it’s the board. Investment is human capital from the family – their talent, leadership and passion. On the business side, it’s their financial investment.

The family strategy was developing talent as the most important tool for sustaining family and business success. In a typical business school, talent development is referred to only in passing. Finance, strategy and marketing – all the big academic business disciplines – are emphasised. However, the real question remains, ‘How do we attract and keep the most capable people in our family and organisation?’

Why is developing talent within the family business so difficult?

Part of the reason lies in accessing objective external help to develop this talent. For example, my daughter is an entrepreneur. Rather than advising her myself, I asked a friend to work with her. I can work with the Cargills or the Batas because, at the end of the day, I don’t have to fulfil the obligations of family to them as well.

It’s crucial that people pursue whatever topics or interests they have in order to develop their unique talents and capabilities. If they decide to enter the business, great. The fact remains, however, that many people shouldn’t be in the family business.

In my opinion, we need to start using new terminology to help focus our family business thinking for the future. We must shift the focus away from ‘family business’ and towards ‘family enterprise’. If you look at the evolution of an organisation, the first generation is usually one individual, the founder. There are normally two or three in the second generation. As families grow exponentially, by the third generation, there are 9, 12 or 18 cousins, but not all of them will work in the core business. The family will have many other enterprise activities.

Some of the family may work in the family office, in the investment arm or for the family foundation for philanthropy. At INSEAD, we are finding many next-generation members want to lead new ventures or start-ups – these enterprise activities are what we need to prepare our kids for.

What do you see as the role of family enterprise in the 21st century?

Demographic and economic indicators point to the continued significance of family business all over the world. The 20th century was about scale and growing large, but the 21st century will be about the quality of growth and why a business exists beyond making money.

Additionally, challenges exist in countries like China, for example. The country’s meteoric growth to become the second largest economy in the world means that many Chinese companies have yet to navigate the transition of ownership successfully.

I believe the need for business as a source for positive leadership in society will increase, especially from the family enterprise sector. This idea of social ventures and social entrepreneurship is all part of the family enterprise concept. Take a look at the Dayton family, the family responsible for Target. They sold the business, but their foundation and the family’s ventures are more powerful than they were 20 years ago. Now, they’re a leading philanthropic voice in the US, and I think this is where the enterprise model really comes in.

When we talk about the Parallel Planning Process, we encourage families to become professionally emotional, which may seem like an oxymoron, but it works. You have to be professional in your governance and strategy, but in your leadership, you have to be caring and emotional. The power of family enterprises lies in their passion, emotion and ability to make a difference in the world.