Interview with Michael Klein:

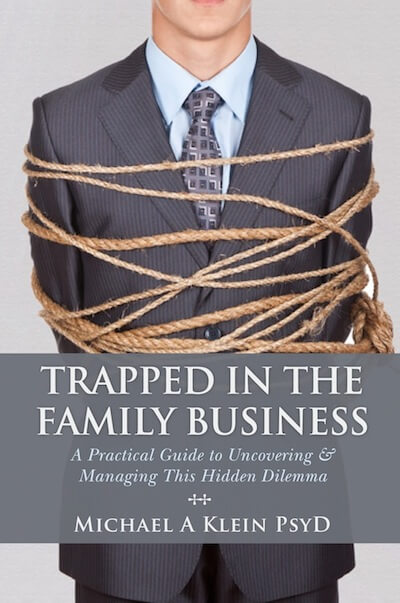

How do individuals get trapped in their family business? Why don’t they leave? And what can be done about it? Based on interviews with family business members, owners, and their advisors, Trapped in the Family Business sheds light on this common yet unexamined problem and offers solutions.

In the following interview, author Michael Klein discusses how he came to write the book, and how family business members can utilize it in order to avoid this common pitfall.

What inspired you to write this book?

I work with financial advisors, accountants, attorneys, and other advisors all of whom had clients who were in family businesses and felt trapped in various ways. After working with several of their clients, I realized that these individuals had little or no awareness of how common these situations are. Over the past 30 years, psychological research has consistently shown that individuals that feel isolated can have a great sense of relief when they know that others share their experiences. This mechanism is known as “universalization.” Once we realize we aren’t as different or unusual as we may have thought, it becomes possible to think differently, ask different questions, and begin to take action. Being trapped in a family business is a textbook example of how important universalization is, and simultaneously, how difficult it is to find. Talking to family about being trapped is rarely an option, and speaking about this outside the family can be viewed as disloyal.

Why is it important to speak about the topic of family members who are trapped in the family business? Is this topic a great taboo or has it been explored previously?

Ken Kaye, a family business psychologist based in Chicago, has written about the “kid brother” syndrome in which a family member’s skill is limited, but family members continually protect him (or her) from this reality. These “kid brothers” eventually become prisoners in their family business and have few, if any, career options. This is a common type of trapped scenario. In my research, I found that there are many other ways in which individuals might find themselves trapped, beyond lacking adequate skills to work outside the family business.

What are the main learning points that family business members can draw from your publication?

Working in a family business can be an incredibly wonderful and complicated career path. Parents AND children need to consider this opportunity carefully, thoroughly, and openly. Only when these issues are discussed and considered can we hope that everyone is well served, and that children can find long-term satisfaction and effectiveness in their work. In many parts of the world, arranged marriages are quite common. I want people to know that often times, working in a family business can be thought of as an “arranged career.” As a result, different generations approach this concept with different ideas and values.

What do you hope your work will achieve for your readers?’

When people know their experiences and challenges are not unique to them, it frees them up to think differently, have different conversations, and take action to improve their situation. That is my primary goal. However, many of my readers are parents who want to make sure they don’t “trap” their children in the business, as well as advisors who want to better understand family business dynamics. I’ve also heard from business students who have read the book to learn about the subtle and not so subtle psychological components of being in a family business.

What is your next project?

Another psychologically complex situation for individuals in family businesses is exit planning (or, transition planning). Advisors and owners seem baffled by the fact that this is such a difficult and challenging process. In fact, there are many researched methods of moving people forward emotionally towards such transitions. While there has been a lot of talk about “psychological readiness” in exit planning circles, the solutions proposed are few, and not based in behavioral science. There are hundreds, if not thousands, of experienced and well-meaning advisors who are trying to understand and sort through these types of complicated psychological issues on their own. Having helped advisors and their clients’ work through these roadblocks, I am bringing together theory and practice into a straightforward guide for advisors who want to assist their clients in taking action on exit/transition planning.